Despite Denials, Serbian Finance Minister Owned Luxury Apartments After All

Despite Denials, Serbian Finance Minister Owned Luxury Apartments After All

It was 2015, and news had just broken that Siniša Mali, the powerful mayor of Belgrade, was linked to $6.1 million in luxury real estate on Bulgaria’s Black Sea coast. He was furious at the media.

Authors: Dragana Pećo (KRIK/OCCRP), Stevan Dojčinović (KRIK/OCCRP), and Atanas Tchobanov (BIRD)

He admitted to owning one apartment in a resort complex there, but insisted that his name only appeared on documents connected to 23 other apartments because he was assisting a client with a business deal. He called a press conference to denounce reporters — and threw in an unusual offer.

“If you determine that I am the owner of any of these apartments, they are all yours,” he said. “You will get the key that very moment.”

The reports that Mali appeared to own millions of dollars in real estate caused a scandal in Serbia since the mayor had no apparent source for the funds. As a public official, his annual salary never exceeded 34,000 euros.

Still, Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić has defended Mali, a longtime ally, against any suggestion of corrupt dealings. “I have absolute trust in Minister Siniša Mali,” Vučić said earlier this year. “I will remind you of all the lies about him, about 24 apartments in Bulgaria. The politicians who led that campaign lied, the media lied.”

But now, six years later, KRIK and OCCRP have uncovered definitive proof that Mali owned the apartments despite his protestations. The evidence was found in documents from the Pandora Papers, a massive leak of documents from 14 offshore service providers, including one used by Mali.

That provider, Trident Trust, is based in the British Virgin Islands, a notorious offshore haven used by the wealthy to shield their assets from public scrutiny. There is no beneficial ownership register in the British Virgin Islands, meaning that the true owner of a company — the person who benefits from it — can keep his or her identity a secret.

The Pandora Papers, a set of millions of documents from offshore corporate service providers, was leaked to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) and shared with media partners around the world, including OCCRP.

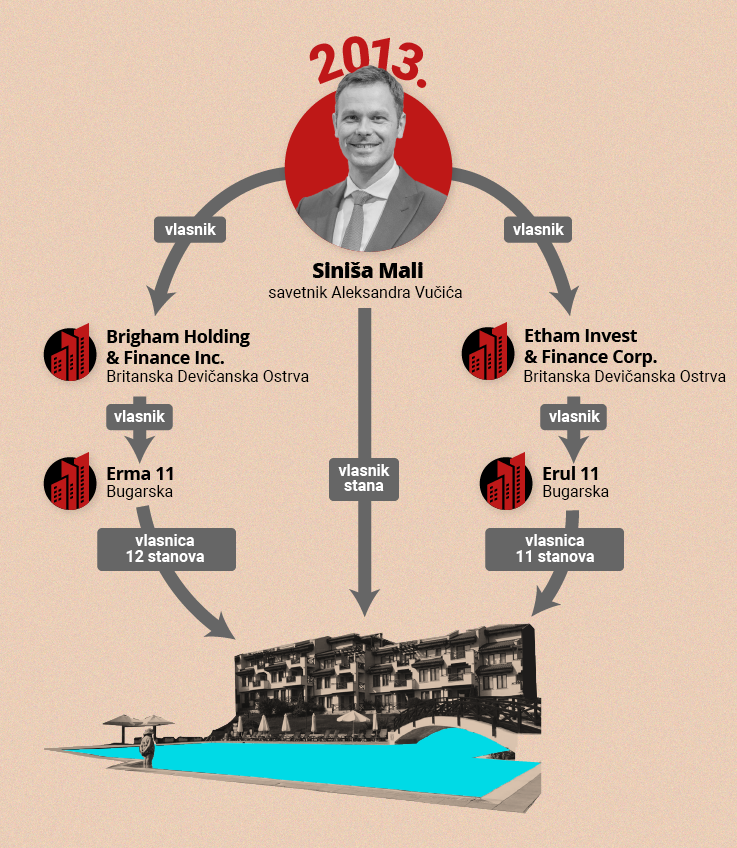

That’s what happened in this case. First, Trident established two British Virgin Islands companies for Mali: Brigham Holding & Finance Inc. and Etham Invest & Finance Corp.

Then, Mali’s two companies bought two Bulgarian companies, Erma 11 and Erul 11, which already owned most of the apartments and soon purchased the rest.

Mali was listed as the director of the British Virgin Islands companies, so reporters were previously able to link him to the apartment purchase through property sales records. But because of the islands’ opaque reporting requirements, it was not clear who actually owned the companies, and therefore the apartments — until now.

Documents from the Pandora Papers reveal that Mali was in fact the sole shareholder of Brigham Holding & Finance Inc. and Etham Invest & Finance Corp.

Mali did not respond to multiple requests for comment on the new revelations.

Mali started his government career in the early 2000s as a special adviser to a department of the Serbian Privatization Agency, which handled the privatization of state-owned companies during Serbia’s transition to capitalism.

In that role, he was involved in an infamous deal that allowed the Russian oil company Lukoil to buy Beopetrol, a Serbian gas company, for 117 million euros, only to immediately take a 105-million-euro loan from it.

Mali represented the Serbian state in the deal, and a local businessman named Srđan Dabić represented Lukoil. It was this same man, Dabić, who co-owned the company that later sold Mali the 24 apartments in Bulgaria.

Soon after Mali bought the apartments in 2012 and 2013, he started selling them. Two were sold in 2013 and 2014, for a total of 120,000 euros. Then, in August 2014, several months after he became Belgrade mayor, he transferred the ownership of his BVI companies to a local lawyer, Ana Panayotova, who sold several more apartments. But even after officially ceding ownership, Mali appeared to retain a connection to the properties — KRIK found his signature on a document related to them from 2015. (He claimed it had been forged.)

The case of the 24 Bulgarian apartments was just one of several suspicious deals involving Mali uncovered by KRIK and OCCRP. Over the years, reporters have learned that Mali illegally obtained state-owned land, helped his father privatize Serbia’s state-owned railway company while he worked at the Serbian Privatization Agency, and took lavish vacations despite a relatively low official salary. KRIK reporters also interviewed his ex-wife, Marija Mali, who told reporters that while he was mayor of Belgrade, her husband would bring her cash of unknown origin that he asked her to stash in her own bank account.

Serbia’s Anti-Corruption Agency opened a case on Mali in 2015 and found evidence he was involved in several suspicious business deals, including one that looked like money laundering. The agency referred the case to the Higher Public Prosecutor’s Office, which asked the Administration for the Prevention of Money Laundering to look into the accounts and transactions of Mali, his wife and children, and any companies he owned or worked for.

The Administration later released a report detailing multiple suspicious transactions. It found that Mali was handling large sums of money well in excess of his official salary. It also found that his lawyer in Bulgaria, Ana Panyotova, was involved in a series of transactions “without clear logic,” some of them connected to deals involving apartments on the seaside.

Despite all this, the Higher Public Prosecutor’s office declined to pursue the case, saying that they saw no evidence of criminal activity.

Mali was promoted to the position of finance minister in 2018. Starting that same year, six of the Bulgarian apartments were confiscated or frozen, first by a local bank and then by Bulgarian tax authorities.

As finance minister, Mali now controls the Administration for the Prevention of Money Laundering. It has not investigated him since he was appointed.